Understanding, Michael Porter

Published on 05/03/2021

By Joan Magretta, released in 2011

I did not know anything about Michael Porter’s work before reading this book. Shame on me. It turns out, the guy is a business mastermind. A lot of companies and schools follow his principles, findings, and guidance when it comes to developing a successful business.

The book is written by Joan Magretta and it is essentially a thoughtful summary of Michael Porter’s main ideas when it comes to developing a business that thrives competition-wise by using sharp-angled strategy. If I had to boil it down into a simple pitch what this book teaches is that: your company must provide unique value. And, the ultimate indicator of competitiveness strength, is profit. If your company is running on positive numbers, then you have a competitive business.

The structure of the book is composed of two simple questions:

1

What is competition?2

What is strategy?

By diving deep into these, we’re presented with the five main components of great strategy:

1

The five forces2

Competitive advantage3

Value creation4

Trade-offs5

Continuity

What is competition?

Well, the usual thing people think when picturing competition is that it is a race with clear winners and losers. But it is just not like that when it comes to businesses. There isn’t such a thing as getting success only when your competitor loses. The mentality that exposes this type of point of view into business making is the“trying to be the best” one.

The right mentality

Porter enforces that a company is deemed to fail if it is trying to be the best. He argues that this is, ultimately, a zero-sum game. The best in what? For who? When, exactly? There’s so much more to it than compared to a battle/war that the best is who survives. Products operating like that end up being more of the same, and no real innovation is brought by. Companies start battling their brains out for market share — which is mostly a vanity metric — and competition is exercised through imitation. Everyone’s been through this no ending catch-up game: “what does company B have that we don’t still? We should prioritize doing that ASAP!”. Ultimately, the customer gets into a position where frequently the decision to use A or B is guided by price. Which one is cheaper? There’s no real differentiation factor between products in a similar given market.

Instead, in order to be really competitive, companies should strive to be unique. This is a central argument of Porters. By being unique, you are creating real value. And by doing that, you end up competing in a multi-dimensional space rather than one-dimensional, like the pricing example I wrote above. The strategy will then be shaped by multiple factors moving around your product and the value you want to create. This will, by definition, make you more competitive. Unique things are hard to copy.

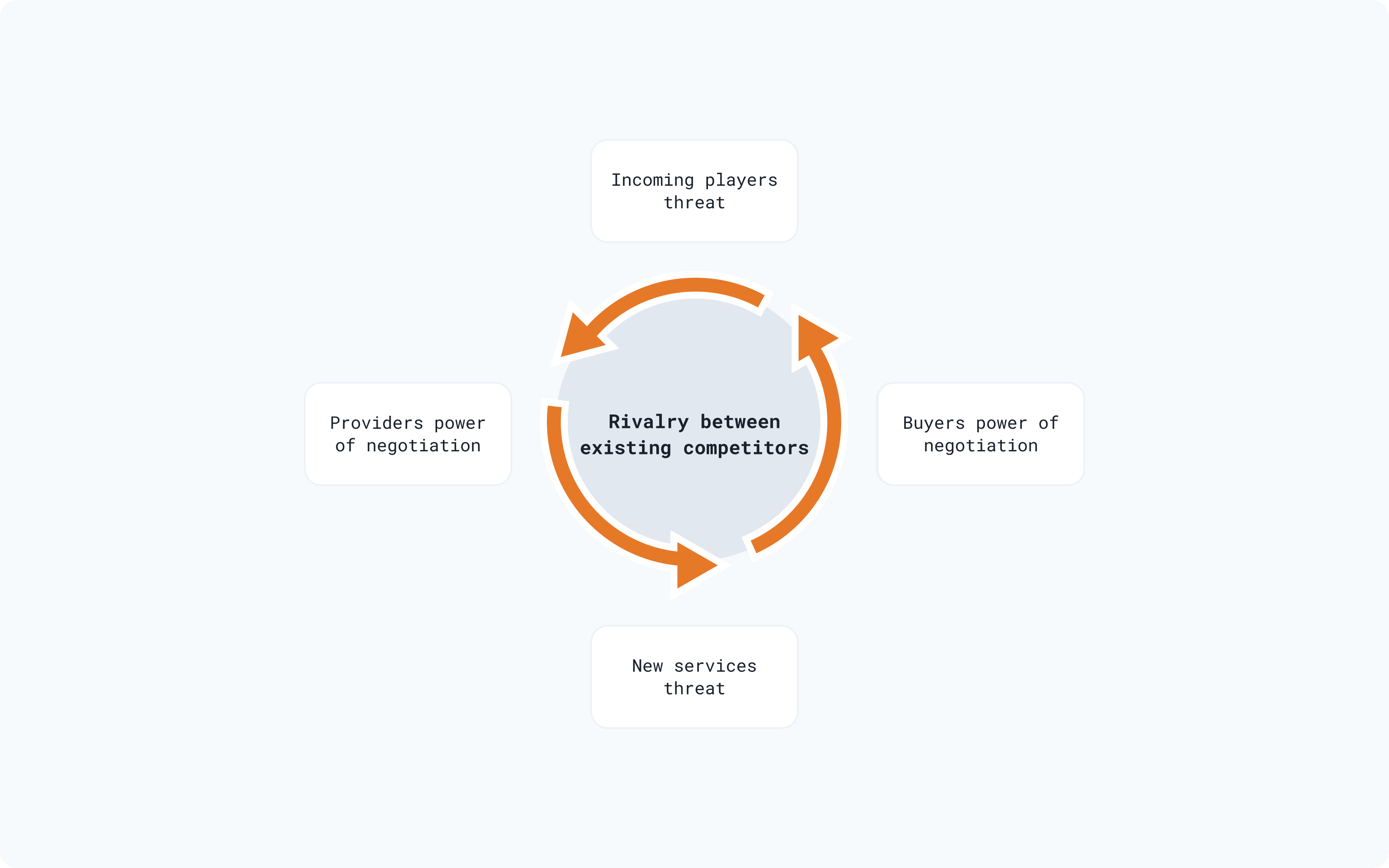

And then, ultimately, to be competitive is to be profitable. That’s another main Porter's argument. It isn’t about winning over your rivals, it’s about capturing the largest amount of profit possible. Porter provides a thinking model for illustrating the dynamics of a given sector, trying to figure out how much profit is there available to capture. He calls it the five forces:

These forces explain the average prices and costs exercised in a given sector, illuminating the average profit to be surpassed. It’s a tool to understand the dynamics of competition in your space. The impact on strategy ends up being that, by understanding the structure of your market sector, you’re better positioned to explore new strategic opportunities capable of refactoring the sector structure itself in your favor. The challenge is figuring out what are the changes that actually matter. The really strategic change is the one that affects altogether the five forces.

Competitive advantage

We learned how to think about competitiveness and what we should study and strive for. Porter then takes us to think, what seems to be key in all his work, about competitive advantage. He argues that you have competitive advantage when, in comparison to the competition, you operate with lower costs and/or charge bigger prices. Without profit being a thing or being on the lookout, you’re not actually competing. We must not forget that. It is about, fundamentally, creating superior value, by using the resources the most effective way.

Two main components of competitive advantage are discussed in the book. They are relative cost and relative price. The capacity to charge a bigger price is to have differentiation. And, ultimately, to be profitable, you need to be able to have lower costs than the competition. Then, strategic choices should be aimed at changing prices and costs in favor of the company/product. This ends up creating a sustainable environment for the company to live in.

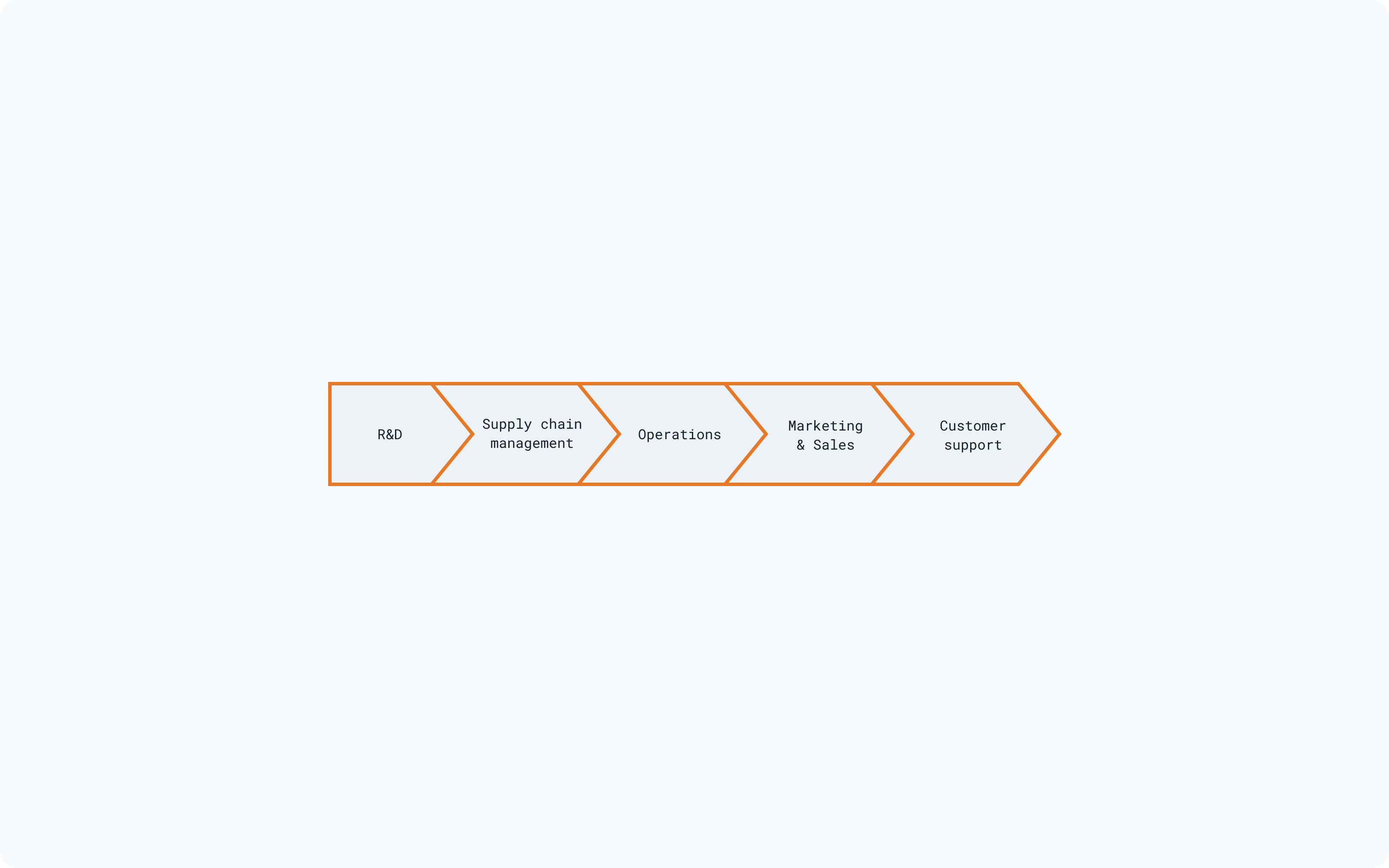

The differences between costs and prices can exist in multiple ways. It comes down to the value chain you’ve created. In other words, it’s the sequence of activities realized to design, make, sell, deliver and give maintenance to your product. They are the relevant strategic activities your company works on to expand the competitive advantage.

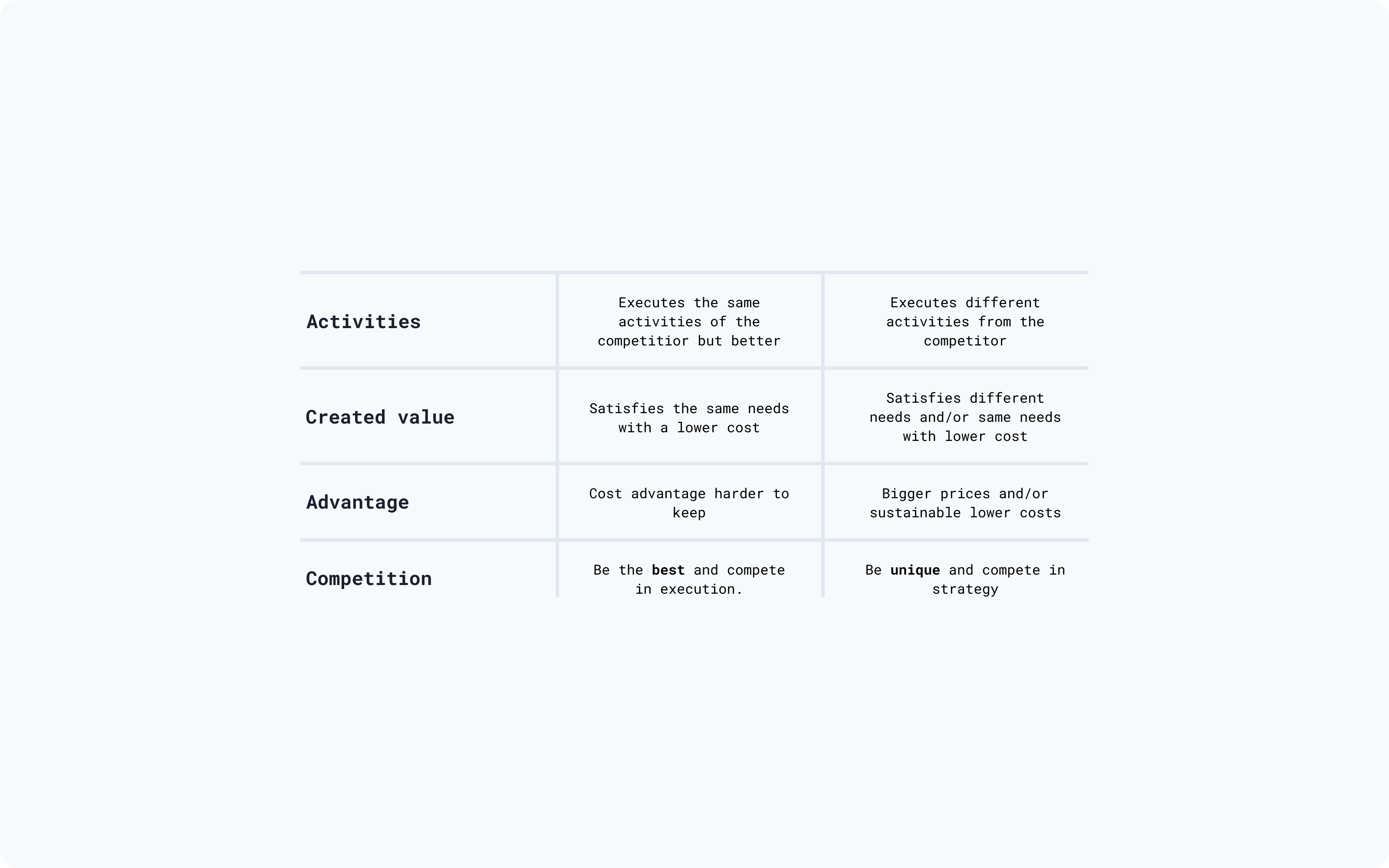

Each activity shouldn’t be looked at as costs, but rather as steps to aggregate some value increase to your product or service. As Porter argues, it’s the moment of truth. What are the activities that, despite creating costs, also create value for customers? Take care looking into it. There are mainly two pathways: a given company can be more performative at executing the same set of activities than another. Or, chose to execute a completely different set of activities. We learned, though, that the first approach is striving to be the best. So, think about what should be done.

What is strategy?

Porter argues that there are five main tests to perform in order to identify great strategies. They are:

1

2

3

4

5

Let’s dive into each one of them.

A distinctive value proposition and custom-made value chain

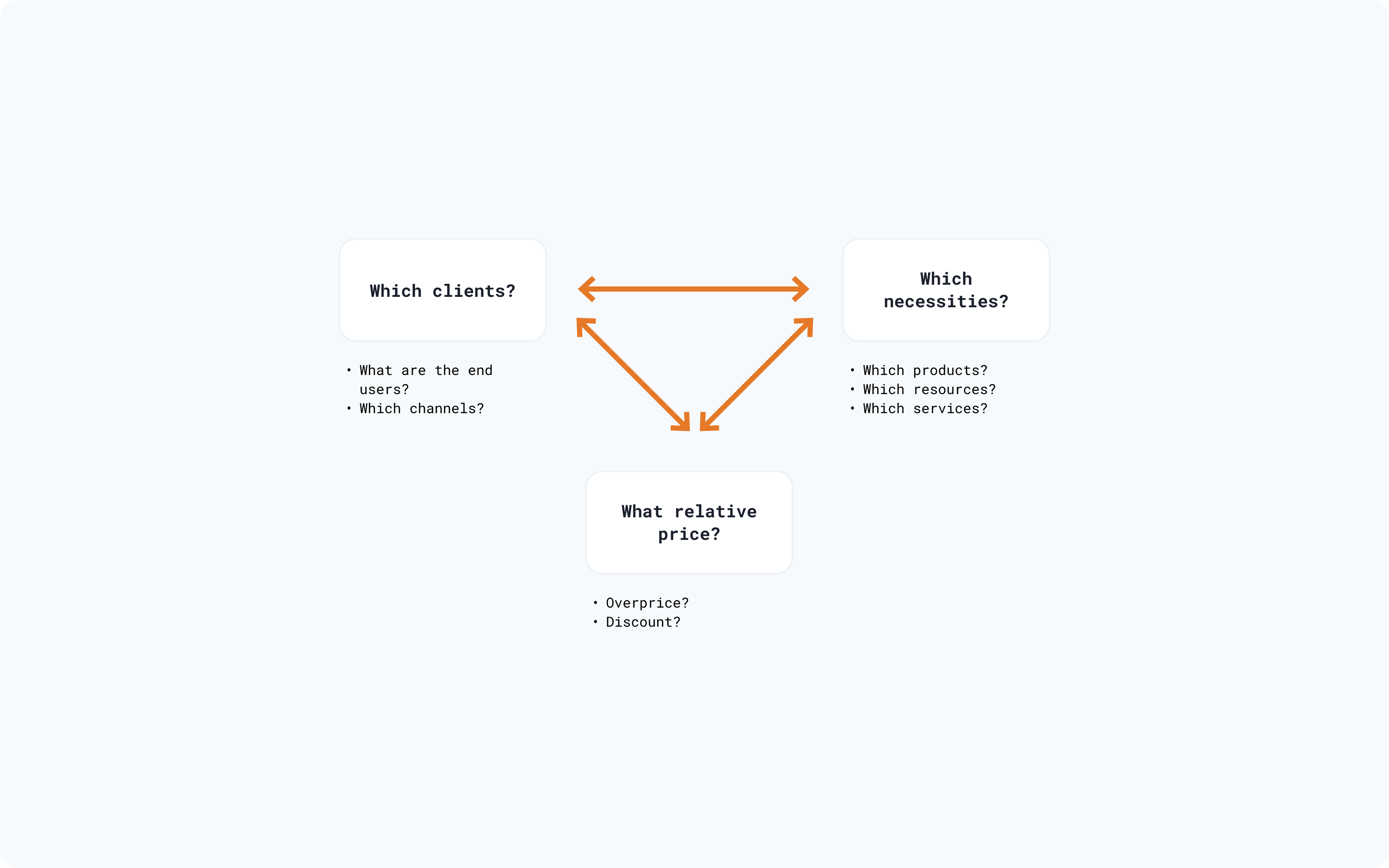

The value proposition is, essentially, an element to a strategy that is focused on the exterior of the company or, rather, on the customers. We have to answer and figure out these questions and their relationships in order to design distinctive value propositions.

The first test of a strategy is asking if the value proposition differs from the adopted by the competition. If a given company looks for meeting the same customers and satisfying the same needs and selling at similar relative prices, then, by Porter’s definition, the company doesn’t have a proper strategy. We’re again competing to be the best here.

Aiming for a given, specific, customer need isn’t enough, though. A distinctive value proposition only will be converted into a significative strategy if the focus is on the activities. By that, I mean: executing given activities differently or executing different activities than the competition. The choices that limit what the company will ultimately do are the ones essential to strategy. They will create headroom for personalizing activities, to deliver those in the best way possible. This creates a unique value chain. Porter offers the example of three different car-renting companies:

Unique trade-offs

This is the one that hit harder for me. Essentially, trade-offs are about what not to do. A hard truth products and companies must face are that they can’t be for everyone if they want to succeed in their competition. When you do that, you end up relaxing in the trade-offs that make your competitive advantage sustainable. It’s in the essence of strategy knowing what you won’t do at all.

There’s one dilemma that Porter discusses that is central, at least for me, in product design as a whole, which is the quality versus cost trade-off. He tells that it seemed a real imposed problem when, apparently, the market in the ’90s, showed that is, actually, fake. Is it possible to be high quality and lower cost at the same time? Is quality free?

Quality ends up being free by removing defects and waste. He argues that this a false trade-off. Companies that are faced with them are the ones that fail at operational effectiveness. When they lack esteem at executing basic activities, it isn't even possible considering quality. The generic needs won't be met.

But when companies work through that, they face real trade-offs. Meaning that adding quality usually means adding new resources, using better materials, and providing better services. And they all usually cost more. The key to this central trade-off is figuring out where you need to provide your utmost quality, the one targeting activities that make you unique and add value to your strategy.

Adjustments and Continuity

Having a clear image of all the aspects I covered before it’s not the endgame. Actually, there isn’t a factual endgame because you’ll need to make adjustments along the way. Good strategies depend on connections between many things. And things that are interdependent.

Adjustments are defined by Porter as being the impact that a given activity has on the cost and value of other activities. It’s kinda tricky to understand. But the point he makes is that it ultimately means that the whole has more importance than any individual isolated part. In other words, the competitive value of individual activities can’t be dissociated from the system or the strategy.

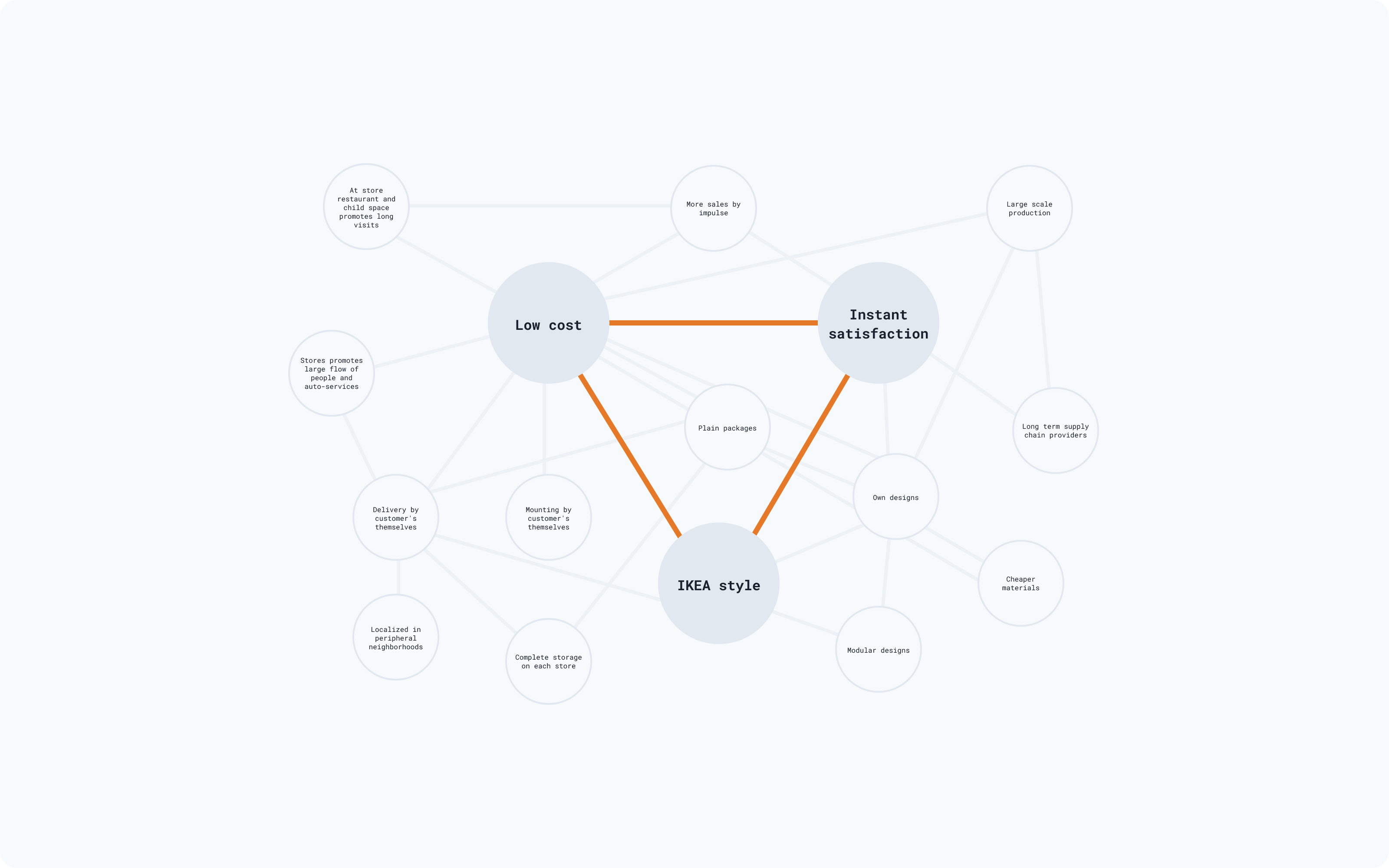

He provides a tool for mapping activities, that aims at linking the meaningful activities into the value propositions. Essentially, an activity map can help identify where to make adjustments. The result of that is a more sustainable strategy and competitive advantage as a whole. Here’s an example he gives from IKEA:

And finally, to wrap it all up, continuity is about making sure that the competitive advantage can be developed over time. And it’s also persisting on a given designed strategy. You might wonder if the strategy itself should be changed along the way. And yes, it should. And it will. But the value proposition must be stable enough. Then, you'd want to have space to change the ways it is delivered. By frequently changing stuff, innovating the methods, continuously upgrading what you do, you won’t have to make bigger and painful changes.

This doesn’t mean a good strategy and value proposition is about knowing what the future holds. This is rather impossible. Porter talks about working in an uncertain environment. It all comes down to having a broad perception about what types of customers and necessities might be relevant in five, ten, or more years beyond. Implicitly, a strategy is about betting — as well as the trade-offs to satisfy it — that these (customers and necessities) will last long enough. But we should not forget that all the exercises said above, the five forces and stuff, are meant to give you this broader perspective, which will then lead you to more secure bets.

Continuity shouldn’t sound like persisting on something pre-defined. Effective strategies are capable of resisting the test of time but there are definitely moments where they need to be changed. Porter argues that these inflection moments are rather uncommon and that companies usually let go of their strategies sooner than later. But it is necessary to understand the conditions that demand new strategies:

When the customer’s needs change.

There’s an example about Liz Claiborne, a 1976 funded company that worked for satisfying an emerging need for women joining the workforce. The company provided safety that women were properly dressed for success. And in their first years, they saw enormous growth and profit. But by the early ’90s, the insecurity of what to wear to work wasn’t a thing anymore for women. Women became more confident about what to wear. At the same time, the workplace clothing paradigm also relaxed. The necessity that Liz Claiborne worked on was considerably gone. From 1991 to 1994, their revenue decreased from US$ 223M to US$83M.

When innovations end up invalidating essential trade-offs from which the strategy lives on

The example here is Dell and HP back in the day. Dell used to fabricate their hardware bits all by themselves and that was a huge thing for their price and product value. But HP started to outsource their components fabrication and also started to focus more on personal-micro-computers. All of this shook the Dell strategy down, making them rethink their products as a whole.

When an innovation, as a whole, overcome the value proposition

Lastly, well, the common example here is Kodak which was completely devasted by digital cameras. And even then, digital cameras were mostly surpassed by smartphones.

Strategy is a path, not a fixed point. When effective, is dynamic. Defines a wanted market result, not all the means to achieve it, Although continuity is essential to strategy, some type of change is needed and absolutely crucial to maintain competitive advantage.

First, you need to be safe at operational effectiveness. If you’re not, the strategy will be irrelevant. Which innovation helps the strategy and which will compromise the singularity? Second, change must happen when new ways to extend the value proposition appear or when new opportunities to deliver the value you’re trying to provide happen. Netflix is a good example of this.

Summing it all up

This book and all of Porter’s work is definitely a bible for product strategy. It isn’t easy but few people actually give this amount of thought into their products and companies. There are countless trying to be the best and they will ultimately fail. Talk about scooter-ride-sharing, huh?

The final reminder Porter gives is that it is impossible to know it all on day one. You will figure out what matters by driving down the road. Therefore, the capacity and flexibility to change are needed. But continuity and a properly designed strategy are also needed because it makes change more effective and viable. Luck definitely is a component of this game, it can’t be denied. But who would be willing to invest in a company that luck is their main strategy?

When you don’t have a strategy, anything can affect your business. Strategy grounds you into deciding what is important because it identifies who a given organization is trying to satisfy, which needs they’re looking to designing for, and how its value chain is distinctively set up to do that at the right price. Strategy makes priorities evident. And if an organization has an objective which people understand, their disposition and sense of urgency about changes are bigger. Great stuff.

Thoughts about this article?

I'm all ears for feedback! Typos? Did something specific get your attention? Anything else? I'd love to hear! Drop me a note somewhere.